The Logic of Peace Can Overcome the Logic of War

October 3, 2023 | Photo by Zaur Ibrahimov on Unsplash

Summary

Differences among actors can escalate to social conflicts if self-regulation gets lost by strong emotions. Affects determine all psychic functions and the behavior of the parties of the conflict. And a destructive attitude and “logic” emerges, the “logic of war”, which intensifies the escalation. The principles of the “logic of war” and the principles of the “logic of peace” are explained in order to de-escalate a conflict if one follows the “logic of peace”. One can use a “window of opportunity” to do the first steps which may lead to peace processes.

Keywords: Affects, collective guilt, de-escalation, differences, dominating emotions, empathy, escalation, logic of peace, logic of war, psychological warfare, sanctions, windows-of-opportunity

1. Differences in themselves are not yet social conflicts

When individuals or communities advocate for their beliefs, interests, or goals and feel that they are being prevented by others from realizing them, the perceived differences can escalate into tensions and social conflicts. However, I do not see the existence of different ideas, beliefs, interests, and goals as a social conflict in itself, but rather as a “problem” that can become a conflict if the actors involved do not handle the differences and resulting stress constructively (Glasl, 2020, p. 17).

Differences in thinking and willing are actually resources that can protect us from one-sidedness: in organizations, different expertise enables a synergy that individuals – for example, in a hospital, a school, or a car factory – could not achieve alone; and in a democracy, respectful engagement with different solution ideas leads to a balance of interests instead of a dictatorship that excludes criticism and opposition. If we were to label the existence of differences in thinking, feeling, and willing as a social conflict in itself – as is done in many conflict definitions (Glasl, 2020, pp. 13 ff.) – then every person would likely have a conflict with every other inhabitant of the earth because their thinking, feeling, and willing probably differ from those of all others. Therefore, according to my understanding of social conflicts, mediation does not aim at eliminating differences themselves but at enabling involved parties to learn how to use them constructively as resources. This requires awareness and an open attitude on the part of the participants as a basis for self-regulation (Bauer, 2015). That, however, can be lost in the midst of conflict.

When people do not constructively manage existing differences, their transactions are determined by thoughts and attitudes I call “war logic”. This “logic,” however, is not guided by reason but driven by emotions. In this process, the psychological mechanisms described in conflict research start occurring (see the summary presentations in Glasl, 2020, pp. 39-54, von Schlippe, 2023, pp. 89-183):

This occurs because the self-regulation of the conflicting parties weakens or is lost completely. Joachim Bauer explains these neurophysiological processes (2011, pp. 53 ff.) as follows: the “I” cannot activate its resources in the prefrontal cortex in the face of strong “bottom-up drives” of the limbic system, leading to an inability to exercise effective “top-down control.”

2. War logic is a form of emotional logic.

My attempt to explain the workings of war logic is based on the work of psychiatrist Luc Ciompi (1999) on “emotional logic”, in which different emotions that coexist are overshadowed by a strong emotion called the “guiding emotion.” In a stressful situation, an actor experiences multiple emotions simultaneously, for example, surprise, curiosity, confusion, and fear. If fear is the strongest emotion, it becomes the guiding emotion and “overrides” the other emotions. Fear now shapes further perceptions, thoughts, needs, and actions. This reflexively leads to behavioral patterns where thinking, feeling, and willing are intertwined. Ciompi describes how the guiding emotion acts as a “glue” that binds perception, thinking, and willing together. The thoughts and intentions constructed under this influence become a specific “logic,” such as fear logic, persecution logic, anger logic, to name a few.

Driven by a guiding emotion, conflicting parties construct a “logic” that appears subjectively plausible and coherent to them, serving two functions:

Using the example of a conflict in an organization, fear logic could express itself as follows:

Or, in the case of a boss’s persecution logic:

In the context of interstate relations, this can be mapped to war logic: How does a government think and act when it observes an opposing government increase its defense budget?

3. Self-regulation is the foundation of peace logic

The essence of peace logic, on the other hand, is that the self-regulation that was effective before the conflict is to be regained and strengthened. One of the most important abilities of self-regulation is anticipation (Bauer, 2011, pp. 56 ff.). A person can anticipate the possible effects of their thoughts, speech, and actions – whether they consciously intended these effects or not – and can act based on their ethical understanding. The ability to anticipate forms the basis, along with vigilant awareness in perceiving, thinking, feeling, willing, and acting.

In communities, social contagion has a fatal effect in addition to war logic. If initially only a few individuals are angry, psycho-social contagion mechanisms can turn this into collective anger (Glasl, 2020, pp. 175 ff.). Luc Ciompi and sociologist Elke Endert (2011) demonstrate this with examples from recent history. Emotions are energies that, through circular feedback loops, cause mutual reinforcement and energy potentiation in individuals and communities, leading to collective hysteria and potential collective aggression. Psychological warfare has always exploited this phenomenon (see Linebarger, 1960; Glasl, 1964; Sailer-Wlasits, 2012, pp. 209 ff.; Bleyer, 2020). Public opinion is an extremely important part of psychological warfare, creating strong pressure for mental conformity through informal control in communities. It takes courage to resist it and even more courage to stand against it.

In the following chapters, I compare the principles of war logic with peace logic, and provide methodological guidance for their application.

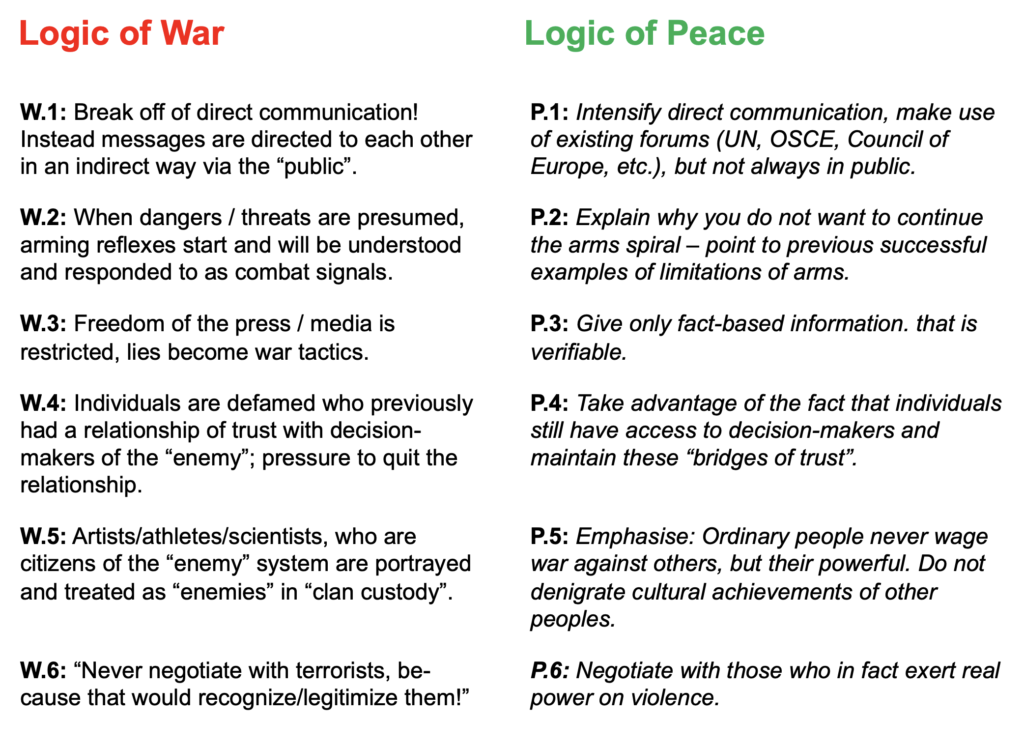

4. How specific behavior can unintentionally contribute to escalation

There are often behaviors exhibited by one party in a conflict that are perceived as unfriendly or hostile by the other party and are responded to in an escalating manner, even though there may not be a deliberate intention to escalate. Therefore, it is important to recognize such behavioral patterns, understand their impact, refrain from them, and respond with a positive action, if one does not want to escalate. I will present six behavioral patterns from W.1 to W.6, determined by the logic of war, and from P.1 to P.6, I will present principles of the logic of peace.

W.1: According to old customs, governments often sever direct communication and abandon existing communication forums/channels when tensions increase. Now they communicate with each other indirectly, such as by delivering a message to the opposing party through the public. However, in times of discord, the risk of misunderstandings increases through indirect communication or messages transmitted through the public, especially since the media may also take up such messages, interpret them according to their own biases, and shape them into “public opinion.”

P.1: It is crucial not to lose control over the meaning of a message, which is why, especially during times of tension, all possible forms and channels of direct communication should be utilized and even intensified. Furthermore, it is essential to take a clear stance when hostile interpretations are circulated through the media. Therefore, existing forums such as international governmental and non-governmental organizations like the United Nations (UN), Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Council of Europe, Red Cross, World Health Organization (WHO), International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), and so on should not be demonstratively abandoned or turned into arenas for accusations or blame. These forums were not created for accusations, as there are no recognized rules for debate and counter-argumentation, leading to a situation where assertions and counter-assertions in the style of wartime rhetoric only complicate matters further.

W.2: In situations of undefined threat, due to the logic of fear, reflex-like gestures are made to demonstrate readiness for combat. In interstate conflicts, there often is an “arms reflex,” taking the form of publicly declared or displayed willingness to arm oneself. Even if this is initially meant by party A as a signal of readiness, it is likely to be interpreted by the opposing party, O, as an expression of A’s offensive intentions, triggering an arms reflex in O. This sets in motion a vicious cycle that continues to escalate.

P.2: If party A recognizes the potential escalation consequences and aims to prevent them, it should clearly state in direct communication that it perceives the behavior of the opposing party, O, as an expression of their security concerns. However, party A should also emphasize that it sees no benefit in further escalating the arms race itself. Instead, party A should mention past shared and effective arms control measures, which have demonstrated that such a trust-building relationship is advantageous for all parties involved. Examples of this can be found in East-West relations, such as the “Helsinki Final Act” of 1975, which led to the establishment of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) in 1995; the “Vienna Document” of 1990, which established regular mutual exchanges of information on the personnel and material strength of military capabilities; or the “Open Skies Treaty” of 1993, which allowed major powers to fly over each other’s territories, using radar and photography to verify the accuracy of the information received.

W.3: War-ready and warring parties require information about the intentions and specific actions of their adversaries to guide their strategies. To hinder their adversaries’ understanding, they obscure facts themselves and disseminate disinformation about their intentions and plans to the public. Consequently, falsehoods and deceptions become integral components of their wartime tactics, although this erodes the overall trustworthiness of the conflicting parties.

P.3: However, to de-escalate tensions and foster further peace negotiation initiatives, a certain level of trustworthiness is indispensable. Therefore, party A should refrain from deceptive maneuvers and only release information to the public that can be independently verified by party O. This is feasible even after periods of mutual disinformation, which are often part of any combative rhetoric, by having party A refer to events that were observed and can be attested to by individuals or institutions not yet militarily involved in the conflict.

W.4: Once a conflict escalates, the social landscape tends to be viewed through a binary lens of friend or foe, where the friend of my enemy is considered my enemy as well. In such a context, individuals who, prior to the conflict, had established a trusting relationship with a powerful figure from a nation now perceived as hostile (for instance, former politicians) often face intense pressure to sever their ties with the influential figures of the opposing party. They are accused of betraying the interests of their own people by maintaining these relationships, even though these trust-based connections may have been beneficial for their own people in times preceding the conflict.

P.4: For the purpose of de-escalation, it is advantageous to value and utilize any existing trust-based relationships with influential figures from the opposing system, using them as a channel for direct dialogue. Friendships can provide access to decision-makers and should be maintained to facilitate the opportunity to provide feedback to those in power about their actions and their consequences. Such feedback is more likely to be heeded because of the trust established with the individuals involved. This can lead to impulses for reconsidering and reevaluating their future course of action.

W.5: War rhetoric often generates collective hysteria and calls for the termination of contracts with artists simply because they are nationals of the opposing party. Simultaneously, cultural and scientific achievements by individuals from the “hostile” nation are devalued, and interactions with them become taboo. Similar treatment extends to scientists and athletes from the “enemy” country.

P.5: Under no circumstances should a collective guilt of all nationals from the opposing country be constructed, for it is not the peoples themselves who harbor hostility and seek to incite wars, but rather the powerful figures within their respective governments. On the contrary, it has proven effective, often in the face of staunch fanatic resistance, to deliberately organize cultural events, concerts, exhibitions, poetry readings, scientific conferences, and the like, involving individuals from both warring states. For instance, in Amsterdam, where Ukrainian and Russian musicians jointly conducted benefit concerts in the autumn of 2022, the proceeds of which benefitted victims on both sides of the conflict’s front lines.

W.6: Governments often refuse to negotiate with illegal paramilitary commanders, terrorists, or violent regimes because they want to avoid giving the impression of de facto recognition and legitimization. This reservation is especially applicable to individuals implicated in war crimes. When negotiations with those who have the authority to wield armed force do not occur, discussions concerning ceasefires, truces, prisoner exchanges, humanitarian corridors, and the like, the cessation of violence and war crimes can only be determined on the battlefield, resulting in a high toll of human lives.

P.6: To put an end to the exercise of violence, the guiding principle should be that negotiations must always involve those who possess effective command authority over the use of force, as they can also issue orders to cease it. An approach following the principle outlined in P.6 has proven effective in various cases (Birckenbach 2023, pp. 180 ff.), such as in Northern Ireland, Afghanistan, Africa, Nepal, and during my mediations in Northern Ireland and Eastern Slavonia (Glasl 2022b). In several instances, it prompted a shift in thinking among various governments and led to peace talks through ceasefires and truces. The value placed on human lives took precedence over adhering to an abstract principle of sovereignty.

The principles of war logic and peace logic described and elucidated here, ranging from 1 to 6, are closely interconnected. In a summarized form, they are juxtaposed in Figure 1.

Adhering to principles P.1 to P.6 can help prevent unintended escalation, which might otherwise be fueled when decision-makers fail to anticipate the potential, even undesired, consequences of their actions and do not counteract emotional logic.

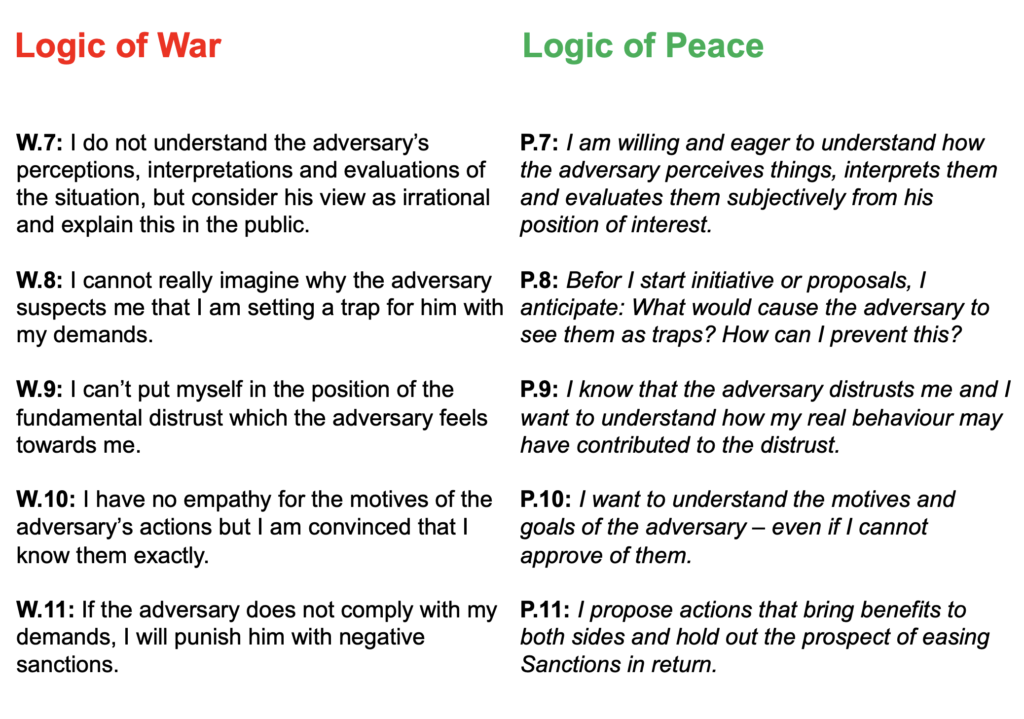

5. How the loss of empathy can contribute to escalation and how that can be addressed

The principles of war logic and peace logic, from 7 to 11, aim to counteract the gradual loss of empathy. Research by Tania Singer (2015) and Richard Davidson (2015) suggests the importance of distinguishing between various types of empathy in mediation. While individuals may possess cognitive empathy, which involves accurately perceiving and understanding another person’s thoughts, this does not necessarily mean they can also empathize with that person’s emotional state. Cognitive empathy relies on different neural pathways compared to emotional empathy. Mediation interventions often assumed that conflicting parties could tap into the emotions of the other through a successful “change of perspectives” (Ballreich/Glasl 2007, pp. 118 ff.). However, practical experience revealed that achieving emotional empathy requires additional interventions, such as “mirroring” or “doubling” (Thomann/Prior 2007, p. 151). A similar situation applies to the ability to intuitively sense the needs and motives of others. While regaining cognitive empathy can facilitate access to emotional empathy, and once emotional empathy is established, intentional empathy can be more easily developed, these three processes involve distinct neurophysiological processes and therefore necessitate different interventions.

In the dynamics of social conflict escalation (Glasl 2020, pp. 203 ff.), it becomes evident that during the escalation stage 1 (“hardening”), cognitive empathy gradually diminishes, propelling the conflict to the next stage. As the dispute unfolds in escalation stage 2 (“debate, polemics”), emotional empathy also fades away. While the conflicting parties may believe they are understanding the opponent’s emotional state, it increasingly involves speculations, attributions, and projections of presumed feelings. In the course of escalation stage 3 (“actions, not words”), intentional empathy is gradually lost as well, leading to the assumption of more and more destructive intentions on the part of the opposing side in the subsequent escalation stages 4 to 9. The tragic aspect is that due to selective perception (Glasl 2020, pp. 41 ff.), the conflicting parties only experience confirmations of their own pessimistic expectations, assumptions, and conjectures.

If party A genuinely wishes to de-escalate, its behavior must demonstrate true empathy toward party O’s perceptions, interpretations, emotional well-being, and needs. The following 5 principles of peace logic, presented in contrast to war logic, illustrate how this can be achieved.

W.7: Party A fails to grasp how party O perceives the entire situation, including O’s self-perception, interpretation of events, and evaluations. When A perceives O’s statements, which reflect a different perspective, A regards them as flawed in escalation stages 1 to 3. However, in stage 4 (“concern for image, coalitions”), A deems them as unreal. In escalation stage 5 (face attack, loss of face) and beyond, A may see them as signs of a pathological, criminal, or diabolical nature. This is because party A believes that anything deviating from its own view of things cannot be real or true. Without cognitive empathy for O, A cannot reach any agreement with O that requires intentional empathy. In such cases, violence becomes the sole determinant of the conflict’s outcome.

P.7: Party A sincerely endeavors to comprehend from what perspectives party O might perceive the situation based on its circumstances. Therefore, A tries to mentally put itself in O’s shoes, attempting to understand how party O, in all subjectivity, might explain and evaluate the situation from its own feelings and interests. A is aware that in a conflict, its perception is likely biased towards negative signals from party O and may be distorted, relying on its own preconceptions. Consequently, party A is prepared to reassess and correct its understanding at any time.

W.8: Parties in a conflict find it increasingly difficult, if not impossible, to empathize with the emotional state of the opposing party, especially from escalation stage 2 (“debate, polemics”) onwards. Therefore, party A struggles to comprehend why party O suspects a trap behind A’s demands and proposals, and why O does not engage with them. When party O makes demands of A, A, in turn, mistrusts that fulfilling them could be detrimental.

P.8: Marshall Rosenberg emphasizes in Nonviolent Communication (Rosenberg 2001, p. 115) that someone can develop empathy for others only when they are capable of self-empathy, which means recognizing and acknowledging their own physical and emotional signals and not suppressing unpleasant (usually negative) feelings. Only then can they open up to another person. Therefore, party A first explores their own feelings and tries to tune into the feelings of the other party O before taking initiatives and making proposals to party O.

Next, party A attempts to imagine from various perspectives how party O might critically perceive A’s ideas and possibly view them as malicious traps. Party A can understand that party O, based on their prior interactions with A, may tend toward caution as a form of self-protection, which is not a pathological reaction but rather a self-preserving stance. Consequently, A checks whether there might be any hidden negative intentions in their proposal. After such a conscientious examination, Party A can openly express that party O might suspect certain deceit in their initiative, and thus, A is willing to explain and subject their initiative to critical scrutiny.

W.9: Party A cannot comprehend why party O inherently distrusts them from the outset, leading to the categorical rejection of A’s statements, initiatives, proposals, and actions without engaging in dialogue. Both A and O often assume that the other side is diligently preparing between confrontations to argue and act from a stronger position in the next encounter. This “pessimistic anticipation” (Glasl 2020, p. 233 ff.) motivates both sides to actively and passively prepare for an increased level of verbal or physical violence. However, through this mutual mental escalation, the readiness for violence on both sides intensifies and sooner or later finds expression in words and deeds.

P.9: When party A seeks de-escalation, it starts from the assumption that both A and party O inherently approach each other with distrust due to negative past experiences. Party A recalls specific transactions where party O had touched a sore spot with A, prompting A to react defensively. Now, A tries to determine where O’s “trigger points” might be and how party O could have been provoked into mistrust and defensiveness. Therefore, A considers which specific “provocative behaviors” they could refrain from and instead, how they should act differently to prevent unintended provocation.

W.10: From at least escalation stage 3 (“actions, not words”) onward, it becomes very challenging for the conflicting parties to intuitively grasp the needs, motives, and goals of the other party. This difficulty arises because they likely project their own fears and assumptions onto the other party. Nevertheless, each party believes it knows exactly what the opposing side wants and, therefore, unconsciously anticipates destructive intentions.

Understanding the genuine intentions of the partner is crucial for de-escalation.

P.10: If party A seeks to engage in dialogue with their counterpart party O to find constructive conflict solutions that are acceptable to both sides, A must be able to understand the true needs, motives, and concerns of party O. If A relies solely on their own fantasies about O’s intentions, O will feel misunderstood and will not be receptive to A’s ideas, especially if they appear to only serve A’s interests.

Because the goal is not to cater to all of party O’s needs, it is important for party A to first gain clarity through self-empathy about their own needs that underlie their interests and expectations. This prevents A from unconsciously projecting their own needs onto party O. Then, it is helpful for A to consider the following questions when contemplating the needs, concerns, and goals of O:

The considerations regarding the various types of needs are further explained in Glasl/Weeks (2008, pp. 159 ff.).

W.11: Each party in the conflict presents the other with demanding requests that must be fulfilled within a specified deadline, and the fulfillment of these requests only benefits the demanding side. If these demands are not met, specific negative sanctions are threatened.

P.11: Even in a situation where there is a tense relationship due to mutual demands and the implementation of sanctions for non-compliance, party A can still de-escalate. A suggests actions to the opposing party O that would be advantageous for both sides and promises to retract one or more specified existing sanctions if party O agrees.

The principles just explained, W.7 to W.11 and P.7 to P.11, are schematically compared in Figure 2. Principles P.7 to P.11 are effective in addressing the loss of cognitive, emotional, and intentional empathy. While a few interventions have been mentioned as examples, the art of mediation, conflict management, and peacebuilding offers many more methods.

Since the war in Ukraine, I have often been reproachfully labeled as “sympathizing with Putin.” Therefore, I must emphasize a fundamental principle that applies to mediators: Understanding does not imply agreement. However, anyone with some negotiation experience knows that I can only reach an agreement with someone if I understand how they perceive and evaluate things, how they feel about it, and what their real concerns are. But, of course, that does not mean I agree with them.

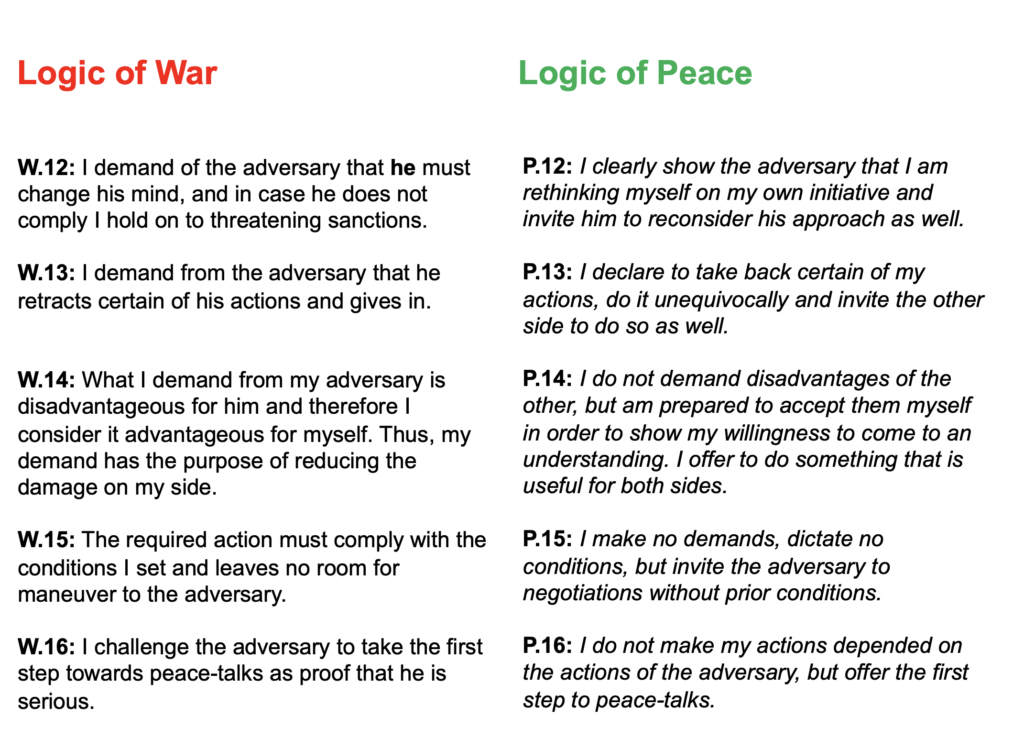

6. Consequences for Action: Give and Take

When the conflicting parties reach escalation stage 6 (“threat strategies, blackmail”), each party demands a change in thinking and behavior from the other, attaching a negative sanction (punishment) to the non-fulfillment of the demand. To demonstrate that this is not merely an empty threat, the potential for implementing the sanction is displayed, which means showing the capability to actually carry out the sanction. When the vicious cycle takes effect, the opposing party responds with a counter-threat, likewise linked to a sanction, and showcases its potential to impose the sanction. This accelerates the escalation and increasingly narrows the scope of action for those involved. However, there is an approach that contrasts with the logic of war, namely, acting in accordance with the principles of peace.

W.12: After negotiations have failed, and the conflicting parties, starting from escalation stage 5 (face attack, loss of face), have no trust that they can advance their positions diplomatically, each side demands that the other must change its thinking – unconditionally and in the way it is demanded – while simultaneously threatening sanctions. If this is responded to in the same manner, a deadlock ensues. In the journal “Sicherheit und Frieden” (Glasl 2014), I demonstrated through the example of NATO sanctions in 2013/14 against Russia that sanctions never lead to a change in thinking but paradoxically result in further hardening and radicalization of thought and action. Nonetheless, sanctions are often justified on the grounds that they are intended to force a change in thinking.

P.12: Instead of exerting pressure on party O through sanctions, party A unmistakably demonstrates through its actions that it is willing to rethink certain points of its own accord. This rethinking may pertain to specific contentious issues and need not entail a complete change of stance. Additionally, party A invites party O to follow suit and demonstrate this through concrete actions. Crucially, this is an honest invitation that does not necessarily have to be accepted and, as such, is not a demand. However, party A remains committed to thinking and acting differently, even if party O chooses not to accept the invitation.

W.13: As part of a threat strategy, party A forcefully demands (and backs it with sanctions) that party O reverses specific concrete actions and continues to concede. Party O is given no room for maneuver and must comply without preconditions.

P.13: To defuse the situation, party A announces its initiative to voluntarily withdraw certain actions and substantiates this commitment through corresponding behavior. At the same time, party O is invited to do the same. Party A remains steadfast in its decision and carries it out, even if party O chooses not to accept the invitation, and A does not respond with sanctions.

Following the principles of P.12 and P.13, President Gorbachev took action in 1986 and achieved a summit meeting in Reykjavik in October 1986 through his preliminary steps. This summit meeting led to breakthroughs in the Geneva arms control negotiations in 1987 (Glasl, 2023, chapter 3.4, figure 24).

W.14: Party A deliberately demands something from opponent O that would result in disadvantages for O. This is because party A sees the harm suffered by O as its own gain, as at this stage of escalation, the conflict parties are driven by a “win-lose” mindset. This means that one side believes it can only win if the other loses something – and that a gain for the other side must be considered its own loss.

P.14: Party A does not demand something that would be detrimental to O. Instead, A is willing, in the interest of de-escalation, to accept calculable disadvantages itself to demonstrate its willingness to break out of the vicious cycle. As proof, party A offers something to O, which it has thoroughly assessed beforehand to be beneficial for both sides. Once again, A extends an open invitation for O to follow this example.

W.15: Party A insists that the opposing party, O, fully complies with the actions demanded according to A’s terms, and it is made clear that there is no room for negotiation or flexibility. Even when there are suggestions for peace talks, conditions are set in advance that must be accepted without discussion.

P.15: Party A does not make demands on the opposing party, O, nor does it set any conditions. Instead, it expresses its willingness to engage in negotiations without any a priori conditions. This approach is crucial because imposing conditions in advance would likely prevent negotiations from taking place, as what has been set as conditions, with no room for negotiation, would itself need to become the subject of negotiations.

W.16: Each conflicting party urges the other to take the first steps towards a ceasefire and peace talks to demonstrate a sincere commitment to seeking peace. However, in the grip of the logic of war, no party is willing to take the first step to end the combative behavior, fearing that it might be interpreted as a sign of weakness. Consequently, in the past, wars have often continued even though both parties recognized it was entirely futile.

P.16: Party A takes initiatives of its own accord, autonomously initiating the first step and thereby not making itself dependent on party O.

7. How can opportunities for de-escalation be utilized?

Even though there often seems to be an impression that the warring actions must be carried out until the bitter end, and that there are only losers, opportunities for brief periods of communication between the parties in conflict do arise. I refer to these as “Windows of Opportunity” because this metaphor illustrates that the window is open just a crack and might possibly be opened wider – but the storm of war can slam it shut again. In the ongoing conflict in Ukraine, several Windows of Opportunity presented themselves:

Such a window opens for a short time when there is at least minimal mutual interest on both sides to find a rational agreement for specific issues in a situation, upon which they can genuinely rely. At this point, a so-called “third party,” such as the UN, UN specialized agencies, NGOs, the Red Cross, neutral parties, non-sanction-involved stakeholders, and others, can intervene to at least expand the area of overlapping interests by one step, with the potential for further steps in the future. This creates concrete and manageable situations for cooperation, serving as small proofs of trustworthiness that can encourage further constructive steps.

However, these Windows of Opportunity are only open for a very short time and must be recognized and utilized swiftly by third parties before they close again, potentially squandering precious opportunities. The chances of success for such initiatives would be much greater if not just one government acts independently – as South Africa’s government did in July 2023, for example – but if multiple mediating powers form an alliance and act together. One member of the alliance may have good access to one party, while another has connections with the other party. Through cooperation, it can be clearly signaled that their primary goal is not just to mediate based on national self-interest but that they represent many people (and the planet!) suffering from the consequences of war. When we consider the devastating effects of warfare that extend beyond the region, impacting ecology, global climate change, food supply, disruptions in the global economy, and more, it becomes evident that essentially all nations are vitally affected by the consequences of war. Many people and their governments, NGOs, and civil society are thus “stakeholders”, meaning they have legitimate claims. They are existentially threatened and must no longer passively watch. This legitimizes them to take action.

When third parties see a window slightly ajar, forming an alliance and promptly acting consistently according to the principles of peace logic can rekindle reason and morality among the warring parties. Thanks to activated self-regulation, conflict parties can overcome emotional logic, which is also in their own interest.

Bibliography

Ballreich, R./Glasl, F. (2007): Mediation in Bewegung. Stuttgart: Concadora.

Bauer, J. (2011): Schmerzgrenze. München: Blessing.

Bauer, J. (2015): Selbststeuerung. München: Blessing.

Birckenbach, H.-M. (2023): Friedenslogik verstehen. Frankfurt: Wochenschau Verlag.

Bleyer, A. (2020): Propaganda, S. 76-90. Ditzingen: Reclam.

Ciompi, L. (1999): Die emotionalen Grundlagen des Denkens. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Ciompi, L./Endert, E. (2011): Gefühle machen Geschichte. Göttingen Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Davidson, R. (2025): Die neuronalen Grundlagen des Mitgefühls. In: Singer, T./Ricard, M. (Hrsg.) (2015): Mitgefühl in der Wirtschaft. München 2015, S. 59-76.

Glasl, F. (1964): Der Vater aller Dinge ist – der Krieg. Zum Konzept der umfassenden Landesverteidigung in Österreich. In: Der Christ in der Welt, 1/1964, S. 6-14.

Glasl, F. (2014): Die Wirkung von Sanktionen auf die Konfliktkonstellation. In: Sicherheit und Frieden (S+F), 4/2014, S. 270-273.

Glasl, F. (2020): Konfliktmanagement. Bern/Stuttgart: Haupt & Freies Geistesleben

Glasl, F. (2022a): Selbsthilfe in Konflikten. Bern/Stuttgart: Haupt & Freies Geistesleben.

Glasl, F. (2022b): Mediation in Krisengebieten. In: KonfliktDynamik 4/2022, S. 281-285.

Glasl, F. (2023): Konflikt, Krise, Katharsis und metanoische Mediation. Stuttgart: Freies Geistesleben.

Glasl, F./Weeks, D. (2008): Die Kernkompetenzen für Mediation und Konfliktmanagement. Stuttgart: Concadora.

Hüther, G. (2006): Die Macht der inneren Bilder. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Hüther, G. (2002): Biologie der Angst. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Linebarger, P. A. M. (1960): Psychological Warfare. New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce.

Petschnigg, E. (2014): „Hätten wir die Bibel jetzt nicht…“ Aspekte legitimierter Kriegsrhetorik im Ersten Weltkrieg. In: Schallaburg (Hrsg.): Jubel & Elend 1914-1918. Schallaburg: Schallaburg.

Rosenberg, M. (2001): Gewaltfreie Kommunikation. Paderborn: Junfermann.

Sailer-Wlasits, P. (2012): Verbalradikalismus. Wien-Klosterneuburg: Edition va bene.

Schlippe, A. von (2022): Das Karussell der Empörung. Konflikteskalation verstehen und begrenzen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Singer, T. (2015): Empathie und Mitgefühl aus der Perspektive der Sozialen Neurowissenschaften. In: Singer, T./Ricard, M. (Hrsg.) (2015): Mitgefühl in der Wirtschaft, S. 40-58, München: Knaus.

Thomann, Ch./Prior, Ch. (2007): Klärungshilfe 3. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt.

About the Author

Prof. Dr. Dr.h.c. Friedrich Glasl,

Born in 1941 in Vienna, Friedrich Glasl studied political science and psychology. He worked in various positions, including in printing companies, municipal administration, and at UNESCO. From 1967 to 1985, he lived in the Netherlands and worked as a consultant at the “NPI Institute for Organizational Development”. In 1985, he returned to Austria and co-founded “Trigon Development Consulting”. He holds the title of Mediator BM and has served as a guest professor in universities both within and outside of Europe. Currently, he is associated with the State University of Tbilisi in Georgia, and he was actively engaged in peace processes in various regions, including Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh, Georgia, Israel/Palestine, Croatia, Northern Ireland, Sri Lanka, and South Africa. Friedrich Glasl has authored books on organizational development, conflict management, and mediation, as well as produced instructional films on mediation. He has received several awards, including the Sokrates Mediation Prize in 2014, the D.A.CH Innovation Prize WinWinno in 2015, and the Life Achievement Award in 2017. You can contact him at [email protected].